Arthur Besse

cultural reviewer and dabbler in stylistic premonitions

- 12 Posts

- 14 Comments

1·18 hours ago

1·18 hours agoNo. Unless Stripe has also implemented the ZK protocol in their whitepaper (narrator: they haven’t) then whatever PCI stuff Stripe does is entirely unrelated to the privacy guarantees implied by phreeli’s new protocol.

2·21 hours ago

2·21 hours agoIf a payment processor implemented this (or some other anonymous payment protocol), and customers paid them on their website instead of on the website of the company selling the phone number, yeah, it could make sense.

But that is not what is happening here: I clicked through on phreeli’s website and they’re loading Stripe js on their own site for credit cards and evidently using their own self-hosted thing for accepting a hilariously large number of cryptocurrencies (though all of the handful of common ones i tried yielded various errors rather than a payment address).

4·20 hours ago

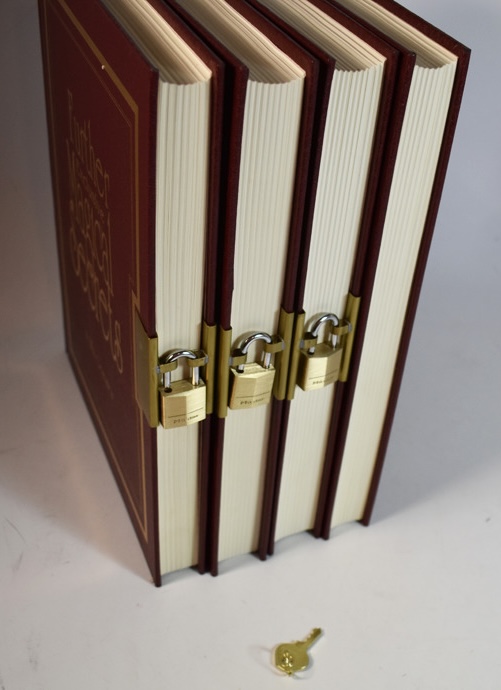

4·20 hours agoSo like, it’s a situation where the “lock” has 2 keys, one that locks it and one that unlocks it

Precisely :) This is called asymmetric encryption, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public-key_cryptography to learn more, or read on for a simple example.

I thought if you encrypt something with a key, you could basically “do it backwards” to get the original information

That is how it works in symmetric encryption.

In many real-world applications, a combination of the two is used: asymmetric encryption is used to encrypt - or to agree upon - a symmetric key which is used for encrypting the actual data.

Here is a simplified version of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange (which is an asymmetric encryption system which can be used to agree on a symmetric key while communicating over a non-confidential communication medium) using small numbers to help you wrap your head around the relationship between public and private keys. The only math you need to do to be able to reproduce this example on paper is exponentiation (which is just repeated multiplication).

Here is the setup:

- There is a base number which everyone uses (its part of the protocol), we’ll call it

gand say it’s 2 - Alice picks a secret key

awhich we’ll say is 3. Alice’s public keyAis ga (23, or2*2*2) which is 8 - Bob picks a secret key

bwhich we’ll say is 4. Bob’s public keyBis gb (24, or2*2*2*2) which is 16 - Alice and Bob publish their public keys.

Now, using the other’s public key and their own private key, both Alice and Bob can arrive at a shared secret by using the fact that Ba is equal to Ab (because (ga)b is equal to g(ab), which due to multiplication being commutative is also equal to g(ba)).

So:

- Alice raises Bob’s public key to the power of her private key (163, or

16*16*16) and gets 4096 - Bob raises Alices’s public key to the power of his private key (84, or

8*8*8*8) and gets 4096

The result, which the two parties arrived at via different calculations, is the “shared secret” which can be used as a symmetric key to encrypt messages using some symmetric encryption system.

You can try this with other values for

g,a, andband confirm that Alice and Bob will always arrive at the same shared secret result.Going from the above example to actually-useful cryptography requires a bit of less-simple math, but in summary:

To break this system and learn the shared secret, an adversary would want to learn the private key for one of the parties. To do this, they can simply undo the exponentiation: find the logarithm. With these small numbers, this is not difficult at all: knowing the base (2) and Alice’s public key (8) it is easy to compute the base-2 log of 8 and learn that

ais 3.The difficulty of computing the logarithm is the difficulty of breaking this system.

It turns out you can do arithmetic in a cyclic group (a concept which actually everyone has encountered from the way that we keep time - you’re performing

mod 12when you add 2 hours to 11pm and get 1am). A logarithm in a cyclic group is called a discrete logarithm, and finding it is a computationally hard problem. This means that (when using sufficiently large numbers for the keys and size of the cyclic group) this system can actually be secure. (However, it will break if/when someone builds a big enough quantum computer to run this algorithm…)- There is a base number which everyone uses (its part of the protocol), we’ll call it

7·23 hours ago

7·23 hours agoMuch respect to Nick for fighting for eleven years against the gag order he received, but i’m disappointed that he is now selling this service with cryptography theater privacy features.

2·24 hours ago

2·24 hours agocontradictory to existing laws (eg section 230).

Section 230 is US law; this article is about the EU and GDPR.

Operating in multiple countries often requires dealing with contradictory laws.

But yeah, in this case it also seems unfeasible. As the article says:

There is simply no way to comply with the law under this ruling.

In such a world, the only options are to ignore it, shut down EU operations, or geoblock the EU entirely. I assume most platforms will simply ignore it—and hope that enforcement will be selective enough that they won’t face the full force of this ruling. But that’s a hell of a way to run the internet, where companies just cross their fingers and hope they don’t get picked for an enforcement action that could destroy them.

4·24 hours ago

4·24 hours agoCan someone with experience doing ZK Proofs please poke holes in this design?

One doesn’t need to know about zero-knowledge proofs to poke holes in this design.

Just read their whitepaper:

You can read the whole thing here but I’ll quote the important part: (emphasis mine)

Double-Blind Armadillo (aka Double Privacy Pass with Commitments) is a privacy-focused system architecture and cryptographic protocol designed around the principle that no single party should be able to link an individual’s real identity, payments, and phone records. Customers should be able to access services, manage payments, and make calls without having their activity tracked across systems. The system achieves this by partitioning critical information related to customer identities, payments, and phone usage into separate service components that communicate only through carefully controlled channels. Each component knows only the information necessary to perform its function and nothing more. For example, the payment service never learns which phone number belongs to a person, and the phone service never learns their name.

Note that parties (as in “no single party”) here are synonymous with service components.

So, if we assume that all of the cryptography does what it says it does, how would an attacker break this system?

By compromising (or simply controlling in the first place) more than one service component.

And:

I don’t see any claim that any of the service components are actually run by independent entities. And, even if they were supposedly run by different people, for the privacy of this system to stop being dependent on a single company behind it doing what they say they’re doing, there would also need to be some cryptographic mechanism for customers to verify that the independent entities supposedly operating different parts were in fact doing so.

In conclusion, yes, this is mostly cryptography-washing. Assuming good intentions (eg not being compromised from the start), the cryptographic system here would make it slightly more work for them to become compromised but does not really prevent anything.

The primary thing accomplished by cryptography here over just having a simple understandable “we don’t record the link between payment info and phone numbers, but you’ll just have to trust us on that” policy is to give potential customers a (false) sense of security.

2·23 hours ago

2·23 hours agoSMS can have end to end encryption

in theory it can, but in practice i’m not aware of any software anyone uses today which does that. (are you? which?)

TextSecure, the predecessor to Signal, did actually originally use SMS to transport OTR-encrypted messages, but it stopped doing that and switched to requiring a data connection and using Amazon Web Services as an intermediary long ago (before it was merged with their calling app RedPhone and renamed to Signal).

edit: i forgot, there was also an SMS-encrypting fork of TextSecure called SMSSecure, later renamed Silence. It hasn’t been updated in 5 (on github) or 6 (on f-droid) years but maybe it still works? 🤷

5·1 day ago

5·1 day agoa summary can be helpfull

No. LLMs can’t reliably summarize without inserting made-up things, which your now-deleted comment (which can still be read in the modlog here) is a great example of. I’m not going to waste my time reading the whole thing to see how much is right or wrong but it literally fabricated a nonexistent URL 😂

Please don’t ever post an LLM summary again.

71·2 days ago

71·2 days agoNot really. The decision only states that a service that allows to publish advertisements with personal information must review these

Did you post this after reading only the beginning of the article? Because, around the middle of it, the author foresees and responds to your comment:

Some people have said that this ruling isn’t so bad, because the ruling is about advertisements and because it’s talking about “sensitive personal data.” But it’s difficult to see how either of those things limit this ruling at all.

There’s nothing inherently in the law or the ruling that limits its conclusions to “advertisements.” The same underlying factors would apply to any third party content on any website that is subject to the GDPR.

As for the “sensitive personal data” part, that makes little difference because sites will have to scan all content before anything is posted to guarantee no “sensitive personal data” is included and then accurately determine what a court might later deem to be such sensitive personal data. That means it’s highly likely that any website that tries to comply under this ruling will block a ton of content on the off chance that maybe that content will be deemed sensitive.

Here are some relevant parts of what the court actually wrote:

67 In the present case, it is apparent from the order for reference that Russmedia publishes advertisements on its online marketplace for its own commercial purposes. In that regard, the general terms and conditions of use of that marketplace give Russmedia considerable freedom to exploit the information published on that marketplace. In particular, according to the information provided by the referring court, Russmedia reserves the right to use published content, distribute it, transmit it, reproduce it, modify it, translate it, transfer it to partners and remove it at any time, without the need for any ‘valid’ reason for so doing. Russmedia therefore publishes the personal data contained in the advertisements not on behalf of the user advertisers, or not solely on their behalf, but processes and can exploit those data for its own advertising and commercial purposes.

68 Consequently, it must be held that Russmedia exerted influence, for its own purposes, over the publication on the internet of the personal data of the applicant in the main proceedings and therefore participated in the determination of the purposes of that publication and thus of the processing at issue.

It seems to me that the fact that the nature of the content was itself advertising is not the relevant thing here, but rather the fact that the website had a commercial purpose is. So, maybe this will only apply to websites operated for commercial purposes? 🤔

(I am not a lawyer…)

A company that publishes ads for sexual services without getting confirmation of consent is a risk for the society and this business model should not be allowed.

Is there something I missed which indicates that the sexual nature of the advertisement was a factor in the court’s decision?

your commitment to the bit is truly laudable 🤣

how about we just try it first

😭

when this is over […] we can finally go back

what specifically do you wish democrats would be more willing to compromise about?

spoiler edit:

i see i have fallen victim to poe’s law 🤦